In operation the “L” fence assembly slides up and down

between a pair of end guide blocks. To

make the sliding operation smooth the ends of the adjustable backer and its

mating edge on the guide blocks get faced with a smooth plastic laminate. The drawing below has red arrows pointing to

the faces that will get the laminate.

These laminate strips are made from a cutoff left over

from a previous project. Because the

laminate is thin and brittle to reduce the chance of breakage when being cut a

sandwich is made with a couple of sacrificial pieces above and below the

laminate like this.

Once the rough blank is cut next is cutting the slightly

oversize narrow strips that get glued to the ends of the pieces. This is what the sandwich looks like with the

top piece removed. Here the first strip

is used to support the left edge of the top sandwich piece so it does not rock

when the cut is being made.

The just cut strips of laminate get glued to the plywood

edges using contact cement. The photos

show how they are being clamped while the cement cures. In the bottom photo the two end blocks are clamped face to face and you can see how the laminate is a little

oversized. It’s oversized because once

the contact cement is applied to both surfaces and allowed to set when you put

the laminate on the plywood it grabs instantly and no adjustment is

possible. Once cured the laminate will

get trimmed to fit the plywood.

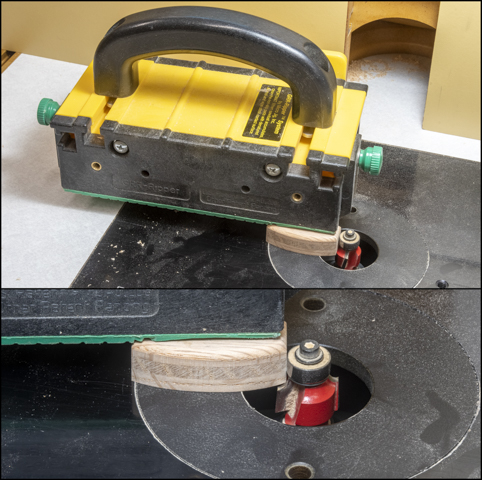

Trimming the laminate is done using the small router with

a straight bit that has a guide bearing on the end guiding the laminate cut flush with the oak plywood. Below the

top photo shows the router, its bit and where just a short section has been

trimmed flush. The inset photo is a

close-up view of the router bit. The bottom photo is after all the laminate has

been cut flush with the oak. Because the

just cut laminate edge is sharp, I need to break the edge with some 220-grit

sandpaper.

Drilling mounting holes for the screws is next. That’s done on the drill press with a bit

that cuts both the pilot hole for the for the screw along with a countersink

for the head. The insert photo is a

closer look at the bit itself without the stop collar.

Once the holes are drilled, the guide blocks get attached

to the backer board. If you look

closely, you can see where the blocks are a little long extending past the ends

of the backer board. That’s done so once

they are glued and screwed in place, they can be trimmed to final length using

the chop saw for a perfectly flush end.

I started by attaching the right one first. After that the adjustable part of the jig

gets set in place then the left block is brought up tight enough so the adjusting

assembly can move easily but not loose enough to wobble. The goal is to have the a fit where the piece

moves easily but snug enough so the blocks keep the piece parallel to the

bottom of the jig.

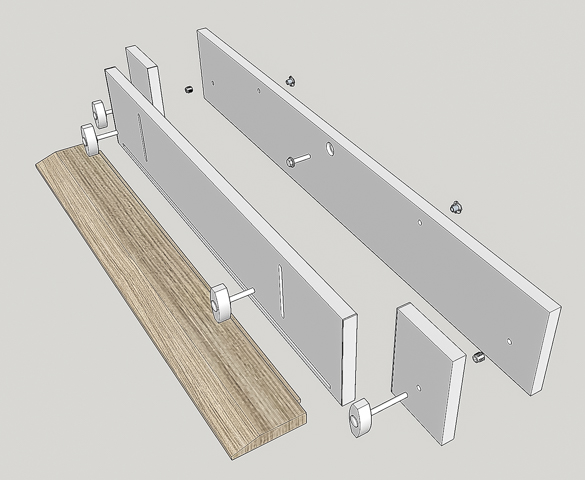

Next is to make four knobs shown in the drawing

below. Two are used to attach the “L”

fence to the table saw’s rip fence straddling assembly and two are used with

the adjustable part of the “L” fence. I

start by taking some thin pieces left over from resawing oak for other projects

and gluing up three layers so the grain in the center piece is at 90 degrees to

the face layers, just like plywood. This

will give the knobs some additional strength to resist splitting along the

knob’s long dimension. You can see the

three layers in the left photo below.

The lower right photo shows how the piece will get cut into six knob

blanks including the saw kerfs.

After cutting the blanks out a ¼” square hole (mortise) gets cut

partway through the knob blank for the square part of the carriage bolt to fit

in. Below in the left photo you can see

how the threads in the bolt transition into a square shoulder underneath the

bolt’s head. The right photo shows the

mortising machine setup used to make the partial depth square hole with the

mortise just started.

After the square mortise gets made a hole for the

threaded part of the bolt is drilled through the blank.

Laying out the curved sides of the knob is next and to do

that the pattern in bolted to the knob blank and it’s outline traced. Below is a side and top view of what that

looks like.

With the knob shape drawn on the top the curved edges get

made using the large disk sander. The

bottom photo is a closer view where the closest edge is almost to the line but

not quite. The face up against the

sander is just getting started. I don’t

completely finish one side before starting on the second side because as the

piece gets sanded the wood heats up and can burn. Working back and forth gives the sides a

chance to cool off a little reducing the chance of burning the edge while

sanding.

When that’s done it’s time to route a small radius on the

top and bottom edges softening them. In

the bottom photo you can see where the top has been finished and the bottom is

ready to go. When the top and bottom

routing is completed, the vertical edges will still be sharp.

Rounding those sharp edges is next and that’s done using

three hand sanding blocks loaded with different grits of paper. Last is some hand sanding using a small piece

of 220 grit sandpaper to knock off the points where the horizontal and vertical

rounded edges intersect plus do any blending as needed where the routed edges

meet the flat surfaces. The photo below

shows each of the four steps needed to go from the mortised and drilled blank

to a shaped knob. These will get set

aside for a while before the carriage bolts get installed.

Next Up – “T”-nut & Threaded Insert Installs – Finishing