With a stack of flattened, square and straight stock I could get started on the project. First are the legs that start by being milled down to final thickness, width and an inch or so long. They will get a taper to one face later after all the mortising and routing is done. The extra length is because there are a couple of mortises that get cut only ¼” from the top edge and I want a little extra material the prevent the piece from splitting while they are being cut.

While the mortising and routing of grooves are similar in

all the legs, they are not the same as the left and right legs are mirror

images. Also, to match the grain the

front and back legs are in sets. This

means each leg only goes in one place.

To keep them straight I write on the top and bottom which corner they

end up at plus writing which face gets tapered.

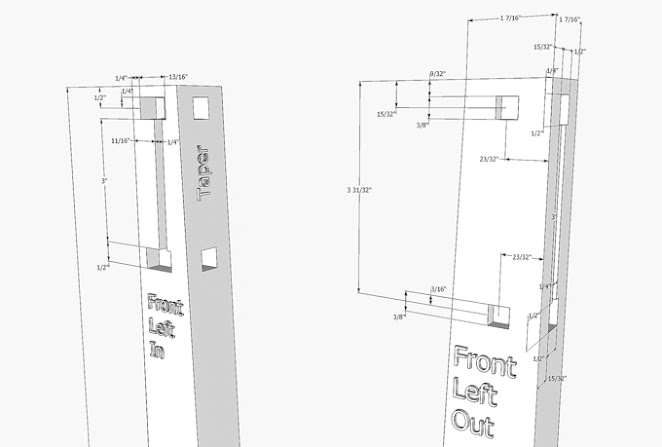

This drawing has all of the needed dimensions for the top of the left

front leg.

This drawing has the information needed to lay out the

bottom of the left front leg. Right now,

I don’t intend to print out a dimensioned set for each leg but will use this

set and make the needed revisions in my head as each leg is marked up. Well, at least that’s the plan and it may

change if problems come up.

Here is the left front leg with the layout all done. On the left is the outer face. If you look close you can just make out the

taper on the left side. The center shows

the inside face of the leg and the right shows the back or inner face without

the taper marked on it. I don’t normally

color in the mortises and slots but did it here for the photo. One down and three to go. While layout for this leg took the better

part of a couple hours what with double checking everything, I think the others

will go much faster.

Here is the way I duplicated the layout. The board on the right is square with the 2x4

in the vice and acts as a stop to keep the two legs aligned. A square is used to transfer the layout lines

for the top and bottom of the mortises.

Since sides of the mortises are all references off the non-tapered face

all I have to do is pull that distance off the drawing and make sure I measure

off that face. It really worked out well

even when making the mirror image legs.

Each leg got easier to mark with the last one taking less than 15

minutes.

This close-up is of the left face of the front legs from

the photo above. The bottom leg is the

original and the top one is a mirror image.

To make all the mortises I will use my mortising machine rather than cutting them by hand as it really speeds things up. Besides I don’t enjoy cutting them by hand that much. The photo on the left is the machine itself while the right photo shows what the specialized drill bit/chisel looks like.

I am going to start with the ½” wide mortises but the

last time I used that drill bit/chisel set it was getting dull so it’s time to

do a little sharpening. Below the photo

on the top left is before where I have marked the surface to be sharpened with

a red magic marker. The one on the top

right is after sharpening and most of the red is gone. The tool at the bottom is what I use for

sharpening. The interchangeable cone

shaped piece is a 600-grit diamond hone.

If the chisel was really in bad shape, I also have a 220 grit one.

Last is touch up the outer face with a leather strop

charged with rouge. The lower part of

the chisel is polished to almost a mirror finish.

Next is to work on the drill part. The photo on the left is before I started and

the right is when done. It had gotten

pretty hot as I finished up the last set of mortises and as I remember it was

smoking a little on the last one.

Sharpening the cutting edges in it is not like a regular twist bit or

most other bits. The closest is probably

a brad point bit. Two tools are used,

first a small fine-tooth file shown at the very bottom and second with the blue

handle is a diamond hone.

Once sharpened the bit/chisel can be installed in the

mortising machine. It is a three-step

process. First, they both are slid

roughly up into place in the mortising head.

The chisel is then set firmly up against the mortising head using a

penny as a spacer and locked in place with the brass screw. The reasoning for the penny will come later.

Second, the drill bit is pushed up against the bottom of the chisel and tightened in the chuck.

Third, the screw holding the chisel in place is loosened, the penny removed and the chisel is pushed up tight to the mortising head. Using a small square, the chisel is squared up against the back fence of the moving carriage and the brass screw retightened. The reason for the penny is to set the needed clearance between the rotating drill and the fixed chisel. If there is not enough clearance between the bit and the chisel when the motor starts the heat generated by the friction between the bit and the chisel will ruin them both. One side note the slot in the left face of chisel is where all the chips will come out. I like to have it face either left or right to allow for plenty of space for the chips to pile up. If it faces either the front or back the chips can get jammed up against the fence or the clamp.