Glue is applied in the mortise, excess is wiped off with

a damp cloth, the pegs are started and last the clamp is applied as shown

below.

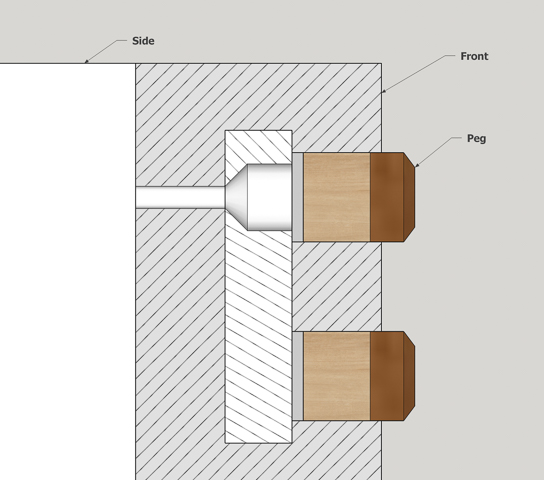

Both door pegs installed looks like this.

The installation of the door pegs completed all of the

woodworking except latches. I was unable

to find what I wanted so decided to make them using rare earth magnets. Plan is to embed a magnet in the case mounted

part of the latch so it’s invisible.

That’s accomplished by making a sandwich. The base layer will house the magnet which

will be covered by a thin oak veneer.

Here is the base layer with the hole drilled for the magnet. For safety a blank about a foot long is use

where one latch is made on each end.

When done they will be cut off to length.

Next is to make the veneer from a piece of thin leftover

oak. The blank was about 1/8” thick at

the start and by using the thickness sander along with a carrier (top photo) I

got it down to less than 2 hundredths of an inch thick (bottom photo). The veneer is made as thin as possible

because the closer the magnet is to the door mounted plate the stronger the

attraction.

Trimming the veneer, a little long is done using a steel

square and a box cutter as the veneer is way too thin to cut with the saw.

Once cut, the veneer is glued to the base layer and held

in place with a few clamps, a caul and a layer of polyethylene to eliminate the

possibility of the caul getting glued to the piece of veneer. Here is that after the glue dried with one

latch still clamped up and the other one unclamped.

Next the latch is rough cut on the bandsaw, cleaned up on

the disk sander and hand sanded smooth. Being consistent with the rest of the

cabinet most of the edges get a small radius routed on them. One place that does not get a radius is where

the latch gets attached on the inside face of the leg. The photo below shows all that work done plus

the magnet that goes in the mounting hole along with its cup. The cup is used to concentrate the lines of

magnetic force.

That’s followed by inserting the magnet in the mounting

hole along with its cup and gluing it in place with a little super glue. To hide the hole, it’s filled using a face

grain plug. The plug is turned on the

lathe with a chuck holding the blank in place.

Once I have the right diameter with just a tiny bit of taper the plug is

parted free.

When I went to make the second plug the blank in the

lathe did not extend out enough to make the second one. The simple fix is to loosen the blank move it

out a bit and retighten in the chuck.

However, when I did that the blank was no longer centered in the chuck. The problem with that is if I turn the blank

true again then it’s too small to make a plug.

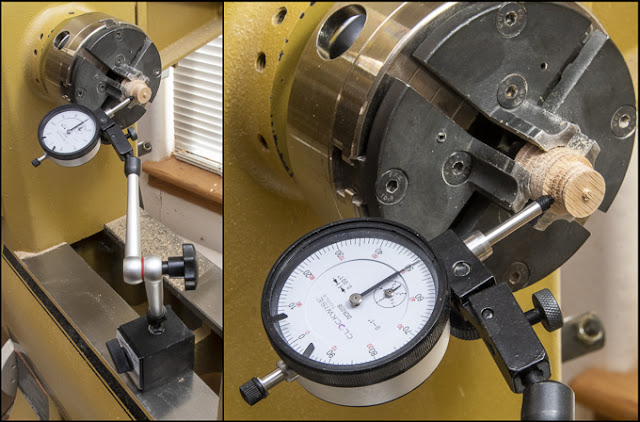

In order to center the blank, I used a dial indicator. The left photo below shows the setup and the

right a close view. As the chuck holding

the blank is turned the dial shows how far the blank is off-center. Small adjustments bring it back to center

then the second plug can be turned.

The plug is then glued in place just like all the

previously installed pegs except once in-place it is sanded flush with the

latch. Once completed there is no sign

of the magnet. Next the latch is cut to

its finished length from the long blank (top photo). Last step prior to finishing is to drill for

the attachment screws. The counter sink

allows for the top of the screw head to be flush with the latch face. The bottom photo shows the front and back of

the latch.

After the latches are finished to match the cabinet they

are screwed in place and a strike plate attached to the door. The strike plate location is marked by

putting it along with the mounting screw pointing out against the latch where

the magnet holds it in place. A piece of

painter’s tape is applied to the door covering where the plate will be

attached. The door is then pressed

against the screw whose point marks the plate’s location on the door. The tape lets me clearly see where the screw

makes its mark. The photo below shows

the latch installed.

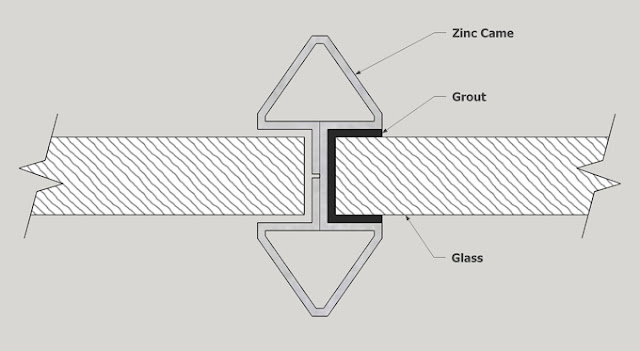

The last bit of work is to run the pick around each piece

of glass in the doors inside and out doing a final trim of the grout. That’s followed by a thorough cleaning of the

glass and zinc using denatured alcohol then polishing with a soft cloth. No shots of that as in the photos the windows

look pretty much the same before and after.

I have to say that this project took quite a bit of time

to complete. It was not a real surprise

as there were a lot of time-consuming details in the design. I knew that going in but it’s those details

that really give the finished pieces their presence. Overall size of each cabinet is, 6’-7” tall X

38” wide X 17 ½” deep. I can just get it

through a regular 6'-8" tall door with an inch to spare although If I take off

the top that will give me another 1¼”.

Once the lacquer finishes gassing off, I will move them into the house.

In order to showcase the stained glass panels and really

bring them to life they need to be back-lit.

I want to use LED strip lighting attached inside the cabinet to do

that. It’s just that so far, I can’t

find the right LED strips. The photo

below shows the desired effect when I hung an LED shop light inside. When I find the appropriate lights and get

them installed, I will update this post.