The approach and my presentation on this project is going to be really different than previous projects. No detailed plans or 3D drawing, not even a paper napkin sketch. Also, I am going to start with the finished item and work backward showing which pieces got made in which order. I had thought about following the making of each piece through the process but decided not to as there was more than a little bit of trial and error. Parts got added, revised and during assembly problems showed up that needed addressing which at times required going back a step or two. The actual woodworking process are fairly simple limited to a jigsaw, Dremel tool and drill plus a few straight cuts on the table and chop saw. There is one exception which is a connector that got made on the lathe that I will touch on when it comes up.

Woodworking generates a lot of dust and chips which if

inhaled can cause respiratory problems.

To minimize airborne dust in the shop all of my stationary power equipment has some sort of dust collection but even so I wear a dusk mask. There is however one glaring exception when

it comes to dust collection, my chop or miter saw. This type of saw (photo below) is notoriously difficult to

get good dust collection on. My saw

came with a small bag connected to the back near the top of the saw that on a

good day managed to capture just a little sawdust. In use it is mostly worthless. When I first mounted the saw in the

workbench, I built a hood around the saw that contained maybe a quarter of the

chips but was ineffective in capturing the rest, particularly the finer dust

that hangs in the air. So, while I was

making things for the shop, I decided to tackle this problem.

The obvious place to start is to find out where the dust went when making a cut. After observing a bunch of cuts looking at just that, I found that a lot of the dust gets ejected right out the back of the saw off the blade. I did note that with the bag on the top port not much sawdust got collected in it. However, with it off there was a fair bit of dust coming out of that port into the hood I had built. My guess is there is little or no air flow through the bag which restricts the flow of the dust into the bag.

There is also some sawdust that gets ejected off the saw blade in front of and to either side of the fence. I believe that’s caused by the zero-clearance wood fence. If that gap is opened up then there was much less dust kicked out to either side but doing that precludes the zero-clearance function which I want to keep.

Next, I considered how the saw is actually used. Way over 90% of the cuts made are with the saw square with the table making a 90-degree vertical cut. Rarely do I tilt or rotate the saw to make miter cuts. However, I do want to keep that functionality available although if required dust collection for those cuts could be omitted.

One feature of this saw is that the two sections of aluminum fence the wood is backed up against when being cut can have a wood extension screwed to each side it which I did. This gives me a longer reference surface when making cuts. Also, since the aluminum fence can be adjusted left and right, I can pull the wood part up to the blade giving me the aforementioned zero-clearance cutting ability. This is beneficial in that the additional support provided to the piece being cut reduces the saw blade chipout as it exits the back side of the cut. In addition, it means that as the edge of the wood fence gets worn and the gap widens during use it’s easy to adjust the fence to bring the edge of the wood so it is tight to the blade. The drawback is the dust collector cannot be attached to the aluminum fence since the fence will need to be adjusted.

With all that in mind I decided to use the existing top

mounted dust port and build a box to capture dust as it comes off the back of

the saw blade behind the wood zero clearance fence. This collection box would not be attached to

the saw itself but mounted to the workbench allowing the wood fence free

adjustment. Hoses will run from both

these points to a common manifold connected to a HEPA shop vacuum

sitting under the saw. Through a fair

amount of trial and error here is a photo of the completed collector box and

hoses with the saw and everything else grayed out. The manifold the hoses connect into is hidden

by the collector box mounting arm in the lower left part of the photo.

Removing the left adjustable zero-clearance fence gives a

better look on how the collection box is put together. The box is made out of ¼” and ¾” thick plywood

plus some ½” and 1 ¼” thick solid wood.

Nearly all of it is screwed together without glue so I can take it

apart and modify the pieces as needed.

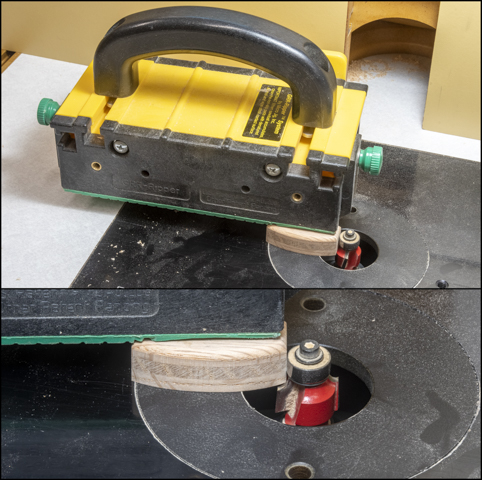

The first piece made is probably the most complex and

hardest. It’s shown as non-greyed out in

this photo. To work right is needs to

fit snugly over the dished-out center part of the saw’s pivot area and behind

the saw fence’s support bracket. It also

has to fit under the saw motor and blade guard when the saw comes down to make

the cut. Adding to the complexity the

part’s profile is not square to the piece but needs to follow the off-center

arc of the dished-out center part of the saw’s pivot area it sits on.

First is to make a simple heavy paper profile to fit the

dished-out center part. This profile is in the

photo’s upper left corner. It is roughly

laid out using the blue finger profile template just below the finished paper

profile. With the paper profile fitted

to the saw the shape gets transferred to the blank in the lower right clamped

in the bench vise. Note here it is

upside down and reversed left to right.

The center board is a full-size drawing of the curved part of the saw

pivot and the horizontal line (top red arrow) represents the face of the

part. This line along with the arcs it

intersects allows me to layout the different angles (bottom two arrows) the

notch needs to be cut at so the piece follows the curve.

After layout the piece gets rough cut out with the jig

saw then the angled transitions get shaped with rasps, files and a Dremel tool

until it fits in place. Here is what the

piece looks like upside down so you can see the angled cuts.

Next Up – Completion & Testing