The next four layers to be made are much thinner that the

others which presents some different problems.

The drawing below has layers numbered 8 and 10 highlighted in blue. What’s not shown is each of these layers is

made up of two rings, one oak and one cherry layer right at 1/8” thick.

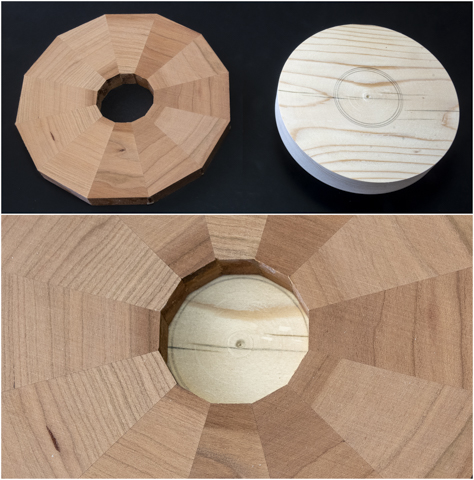

Because these layers are so thin the hose clamp used to

pull the segments together has a tendency to slip off as it is tightened. Getting around that problem required making

the jig shown below. Four spacers just

1/64” taller than the hose clamp’s band gets clamped to the jig. This lets the segments and the hose clamp

move around as the hose clamp gets tightened but keeps the hose clamp from

riding up and popping off the segments.

The right photo is a little closer view.

Another problem with the thin segments is that when the

hose clamp is tightened the segments do not lay flat but get a little

wavy. That’s solved by using a piece of

MDF as a caul after first laying down a sheet of 6 mil polyethylene plastic on

top of the segmented ring. The plastic

keeps the ring from getting glued to the MDF.

With the MDF caul in place, the red handled clamps are snugged down, the

hose clamp tightened and the red handled clamps tightened the rest of the

way. Here is what all that looks like

completed.

Since all four of the layers are the same size, I decided

to cut the segments all at once while the tablesaw jig is setup then do the

four glue-ups using the gluing jig before moving on. The down side is because I let the glue cure overnight it takes four days to glue-up the rings. Once all four all done, they get run though

thickness sander. However, since they

are thin and a bit fragile a carrier with support blocks shown here is used to

support and hold them while being run through the sander.

Here the four rings are sanded, done and ready to be

glued on.

Gluing on the thin cherry and oak rings are next. They follow the same procedure as the others

with one exception. Since the ring is

somewhat flexible the MDF caul is used (red arrow) to keep the layer flat with the polyethylene

between it and the layer to make sure the MDF and the ring don’t accidently get

glued together. The same process is used

for the next thin oak ring.

Cutting the already made blocks in segments for the four

feature rings takes a little planning so they come out nice and flat when

glued-up. When making the regular rings

the board is flipped top to bottom after each cut. In the photo below you can see the cutting

jig on the table saw with one piece cut and three cut pieces lined up near the

bottom. When these pieces are assembled

into a ring, they will lay flat even if the saw blade is not absolutely set at

90 degrees to the table because if there is an error it gets cancelled out by

the way the segments are cut. Bear with

me for a bit as I go through how this works and why it’s important when cutting

the segments for the feature rings.

As much as I try, I know the table saw blade is not

absolutely perfectly 100% square with the table. It’s very close, close enough so I can’t

measure an error when making a cut.

However, because the rings are made from 12 segments there are 24 cuts

and any error when making a cut gets multiplied twenty-four times so a really

small error gets magnified a lot. As an

example, let’s assume that the blade is off an exaggerated amount of say 10

degrees like in the drawing below. When

the end cut is made as in the bottom photo the edge of the segment ends up with

the jig’s 15-degree angle plus the 10 degrees the saw is out of square.

Next the board is flipped top to bottom, slid over to the

stop and the segment is cut to length which is the piece to the right of the

saw blade in the top drawing below. This

piece’s edges are not square and do not have parallel edges. To make the second segment the board is

flipped top to bottom and then the second segment is cut with the results shown

in the middle drawing below. Last is to

flip the just cut segment top to bottom which is shown in the bottom drawing. Now when the two cut pieces are glued

together the angled edges of the segments cancel each other out resulting in a

flat glue up.

This method only works when the segments get cut from a

continuous board but the feature rings are not made from a continuous board,

they will be made from the already rough sized individual blocks.

The first segment follows the same process as the ones in

the regular rings. First, one end is

trimmed using the jig to make the 15-degree angle shown in the top photo. If you look in the saw slot in the jig you

can just see a line that represents the cut of the hypothetical 10-degree out

of square saw blade. The piece is then

flipped top to bottom and the other end cut to make the tapered segment (bottom

photo). On the vertical face the pencil

lines show how the piece would look like a wedge. Now if the next piece were cut the same way

that wedge shape would compound and not cancel out. The result is when the segments glued

together a shallow cone would be created rather than a flat ring.

In order to make a segment with complimentary angles to

the first one I need to reverse the cuts or make the first cut with the blank’s

bottom face up rather than down like the first one. That setup is shown in the top photo. Note that this blank has the maple side up rather than the previous piece which started with the cherry face up. After the first cut the blank is flipped top

to bottom and the second cut made per the bottom photo.

Put side by side you can see when the cuts are made as

described above the adjoining faces (red arrows) will cancel out any minor

variances from a non-square saw blade.

The result is a self-compensating joint that will mesh creating a flat

glue-up. Now all I need to do is make

sure that all the even numbered blanks are cut one way and the odd numbered

ones the other.

Next Up – Making Feature Ring Segments