With the bevels made on the cap blanks the pattern is used to lay the four caps on them. Only wrinkle here is due to the bevel only one side of the pattern can be traced at a time. After the first side is done the pattern is rocked on the center line so it lays flat on the second bevel being careful to make sure the pattern does not shift so the other side can be traced.

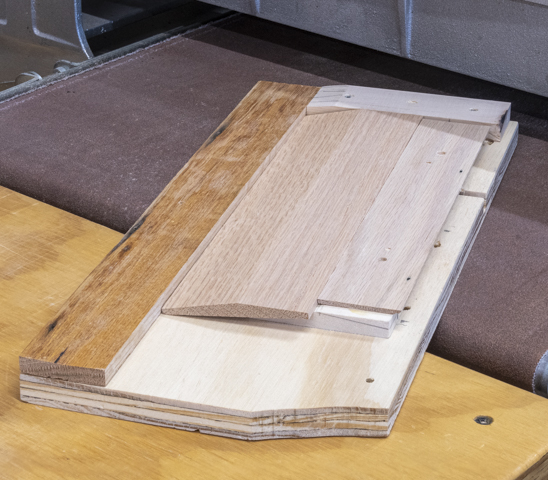

The caps get cut out using the scroll saw just like the pattern. Here is the scroll saw along with what the blank looks like after one of the caps are cut out.

That’s followed by using the big disk sander to clean up the edges and blend all the curves together. The bottom photo shows that the scroll saw left a pretty good edge although it does not follow the line exactly. Now I could have spent more time cutting close to the line but I would still have to finish cleaning up the cut on the sander blending the curves and it’s just easier to cut close to the line and smooth the edges with the sander.

Below the photo on the left shows what a cap looks like before sanding and the on the right is after.

Next the edges of the caps get a small radius hand sanded on them to make the edge look softer, thinner and to continue the general roundness of the piece. Since the caps are too thin to use any power tools the edge has to be put on by hand using something like small detail files or sandpaper. Some testing led me to use sandpaper rather than files or a scraper. The edge work starts using 80 grit sandpaper to rough out the shape, followed by 120 grit paper to refine the edge and finishing up with 220 grit paper. The top photo shows a completed cap and the bottom photo shows the caps just set in place.

Applying the first coat of India ink is next. The top photo shows everything ready to go and the bottom shows the finished first coat. There are some white specs that are pores in the oak that did not get dyed but that’s normal and will get touched up.

The next day all the black pieces get the odd white specks touched up. Additionally, the center part of the oak dowels that are exposed when the bowl and the body are connected get a coat too. They are in the lower left next to the India ink bottle and have the ends wrapped with blue masking tape. This is to limit the ink and lacquer application so there is bare wood available for gluing.

While I was working on the dowels there are a couple of finishing touches. The top photo shows a small hole in the end of the dowel and that’s to provide a little space for any extra glue to go to when the pieces are assembled. The bottom photo shows two end cuts made on the scroll saw to allow a path for the glue to escape to the center hole.

Next is to start gluing the caps onto the body. Because when installing the caps there is little or no room for error since if the small overhang is not just right it’s going to be very apparent. Also, when applied the glue acts like a lubricant and pieces can easily slide out of position during clamping. To keep this from happening I tested four ways using scraps to keep the caps in place while the glue dries.

- I started by trying to use the pneumatic pin nail gun on a sample to shoot a very thin 22 gauge (.0253”) headless nail through a cap cutoff into a scrap of the body. The problem with this is when the nail is shot in place the head is just a tiny bit below the surface which leaves a small hole in the cap. As the cap is small to begin with the hole would be fairly obvious.

- Using a dab of hot melt glue in the center of the cap to hold it in place until the glue cures worked better. However, this got eliminated because of the short amount of time for adjustment before the glue cools off and the ability to make adjustments is lost. Also, if not enough downward pressure is applied before it solidifies there can be a gap between the cap and the body.

- Using super glue to hold the piece in place while the wood glue cures didn’t work to well. In some testing the spot of super glue that was available wasn’t big enough to hold the pieces tightly together. It also didn't allow much time to make adjustments before the glue set.

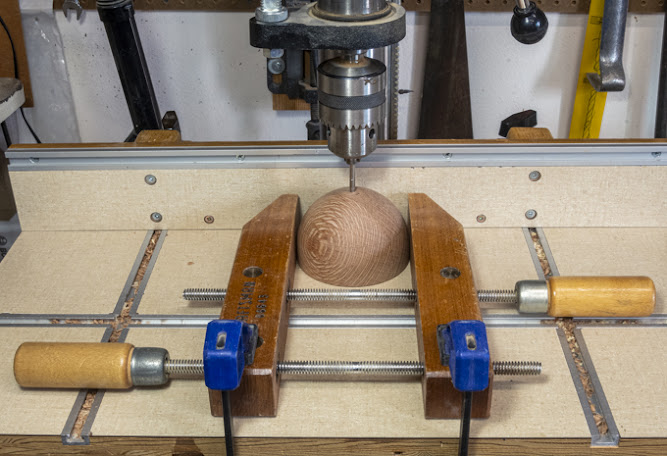

- What I ended up doing was to shoot two of the small pin nails part way in the body where the cap gets glued on. The pictures below show what I mean.

Next is to very carefully to locate the cap exactly where it needs to go taking all the time needed. Once in the right position the cap is pressed down onto the body and the pins poke reference holes in the underneath side of the cap. The two red arrows point to those holes.

Now glue can be applied to the cap and using the locating pins in the body the cap with its holes can easily be put back in exactly the same place. In addition, the cap won’t slide around while being clamped. The photo shows the cap (red arrow) clamped in place. Only one cap at a time is glued in place to eliminate any chance of it moving.

Finishing everything except for the lid and its finial, which I am still doing designs for is next. Preparation of the shop includes blowing off the equipment, giving the floor a good cleaning. The workbench and the places where the sprayed pieces are set to dry after spraying along with the cardboard sheets used to protect the workbench from overspray all get wiped down with a damp cloth. A satin finish lacquer will be sprayed on and probably three coats will be needed. This photo shows all the pieces final sanded and ready.

This is my typical assembly of items for spraying lacquer. On the far left is the gallon can of lacquer with a smaller bottle used for mixing since it’s easier to pour out of. Side note, the green line on the side of the can shows how full the can is. To its right at the back is the lacquer thinner and in front of it is a small bottle for mixing. On the right at the back is my mask with N100 filters that also remove organic and acid vapors. In front of the mask is a bottle of lacquer that has about 25% by volume of the thinner added and is ready for use. In front of that bottle is a smaller bottle that is attached to the air brush used to spray the lacquer onto the pieces. Last, at the front is a pair of gloves used to protect my hands when spraying.

Next Up – Spraying Lacquer, Assembly & Finial Options