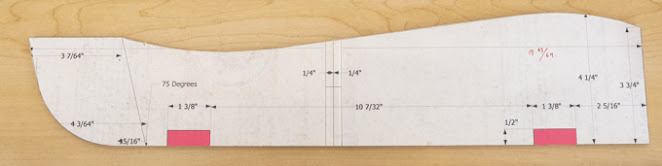

Assembling the seat and back braces is next. All three of them follow the same procedure

but the photo below is of the second one being done. That’s because the first one is used as a

jig to make sure all three are identical when finished. This photo shows a dry fit with the two

pieces clamped together and screws temporarily run in.

Here is a closer view of the joint. At the bottom of the silver clamp is a wedge

cut to the same 75-degree angle as the half lap joints. This allows the clamp to have a flat surface

to bear against at both ends. There is

a similar wedge for the red clamp. After

the dry fit the clamps and the screws are removed. A Type III waterproof glue is spread on both

halves of the joint then everything is reassembled. The screws are really just there to provide

clamping pressure until the glue cures.

After the glue cures the screws are removed and 7/16”

diameter holes are drill through the joint for dowels to be installed as joint

reinforcement. Because the screws left a

hole bigger than the point on the brad point drill I am using to drill the

holes a circle is drawn centered on the hole so the edges of the drill bit can

be used to locate the hole. The top

photo shows the drill press setup and the bottom photo is a closer view that

shows the edges of the drill lined up with the drawn circle.

I choose white oak as the dowel material since it is a

hard wood and is resistant to moisture damage. They start with a 5/8” square

blank mounted in the lathe that gets turned down to a ½” diameter.

The blank is then reversed in the chuck and the square

end turned round. That’s followed by

turning the blank down to a hair over 7/16” in diameter using a 7/16” open-end

wrench as a guide and a parting tool to make reference cuts as in the photo

below.

Using these reference diameters, the dowel is turned

smooth with the last little bit carefully removed. A sample hole drilled in a scrap is used to

gauge when the fit is right. Once the

diameter is just right the dowel length is marked and it’s cut off with a

fine-tooth coping saw.

To install the dowel waterproof glue is spread inside the

hole and a little on the leading edge of the dowel, it’s then driven in with a

mallet and left to dry.

The next day tape is added next to the dowels to raise

the cut just off the brace’s surface since I don’t want to scratch up the base

material. The saw is a Japanese pull saw

that has no set to the teeth. Here the

right dowel has been cut off.

After peeling off the tape the dowel is just the thickness

of the tape proud and that’s removed with a very sharp chisel as shown in the

top photo. The bottom photo shows after

both dowels have been trimmed and the surface sanded to remove the smeared

glue. I am not worried about there still

being some soaked in glue remaining since the piece will be painted rather than

given a transparent finish.

Here’s the three seat/back braces done, for now. I may route a small radius on the

back and bottom edges of the brace. Work

on the braces will stop while the slats are made. They need to be mostly done before the exact

spacing can be determined. Also, there

are several ways to attach the slats to the braces and that has not yet been

decided.

Cutting the 17 slats for the seat is next. They come from four different 2”x6”x10’

pieces. For those that don’t know a 2x6

is really 1½” x 5¼”. The plans call for

the slats to be 1½” wide and 1” thick. I

am guessing that by the time I get done surfacing the boards they are going to

be maybe 1/16” narrow. There will also

be some of the overall 5¼” width lost to straightening the edges but that

should not be a problem. A short

explanation on how the slats get cut from the 2x6. As noted above a 2x6 is really 1½” thick

which is the final width of the slats.

So, when I start ripping 1” wide pieces off the 2x6 blanks that’s really

the thickness of the slats.

It did take the better part of a day to do the following slat preparation work:

- Cross cut the 2x6’s in half

- Straighten and make parallel the long edges.

- Rip to blanks either two or three slats wide to work around knots and to make any cupping less pronounced prior to surfacing.

- Surface the blanks to final thickness which will be the final slat width when the blanks are ripped again. The final thickness of the blanks or the final width of the slats ended up as 1 7/16”.

- Straighten the blanks that warped (about half) due to internal stresses being released when ripped.

- Since the blanks are oversize a final review of which edge to work from needed to be made when ripping to minimize flaws in the final slat.

The photo below shows all that done and ready for the

next step which is to rip to final thickness but that will wait until tomorrow

to see if there is going to be any more wood movement that has to be addressed.

Next Up – Making Slats & Slat Attachment Options