After cutting the sides and bottom to their final length

plus 1/32” (for post gluing trimming) the glue gets applied to the bottom three

quarters of the width of the joint. It

will be easy to clean the glue squeeze out off the bottom face of the box but

not so easy on the inside so I want to limit squeeze out there. A drop of glue is put on a scrap wood block

and application is done with a toothpick.

The white mark in the top center of the walnut bottom is my reference

mark for piece registration.

Here's what the clamping for the glue-up looks like. The reference mark gets matched up, the ends

get checked to make sure they are flush with the side and the bottom is flush

or just a tiny bit lower than the side.

That’s because it’s easier to make bring ¼” thick side flush versus

working on the whole bottom’s width.

Spacers cut from scrap get inserted at the top of the box help keep the

sides and bottom square. A check with a

square confirms that. Once the glue

cures overnight the other side will get glued on the same way. I choose to glue the sides on one at a time

to minimize the chance of getting something out of alignment during

clamping.

The next day the clamps are removed then the bottom and

sides are checked to see if they are absolutely flush. Not surprisingly they need just a light touch

to bring them all flush. With that done

the ends can be cut and fitted so they are snug with a little clearance at the

top to allow the lid to easily slide through.

Here’s what the clamping setup looks like for them.

After the glue cures the end panels are sanded flush with

the sides as shown here. While flush the

grit on the disk sander leaves some circular scratches that will get sanded out

after the edges are rounded.

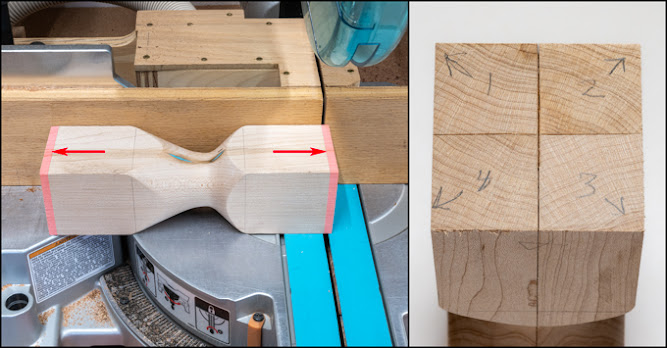

Rounding the edges is done on the router table with a

1/8” radius bit. Rounding the ends is

done first because during routing the end grain of the sides can splinter when

the bit exits the cut. If it’s not too

big then the flaw will get cut away when the long dimension is rounded

over. Since the ends are narrow a backer

board is used to assure the box stays square with the fence while also

providing additional support to the walnut edge when the bit exits the

cut.

This is what the box looks like with the edges

rounded. The router does a pretty good

job except for the top four corners of the box.

The red arrows in the inset point to where two of them have been sanded

round. They weren’t routed as I was

concerned that the tiny corner would get damaged during the process.

After final sanding applying a finish to everything is

next. The Christmas ornaments get three

coats of a wipe-on poly finish. I didn’t

spray them because I can’t get the spray gun inside the ornament and the inside

shape is too complex to try and spray it from the outside. Here are the completed ornaments.

Before spraying I was checking the refrigerator magnets

and one of them just didn’t look quite right.

The top part of the walnut, maple and cherry one looked out of

scale. It bothered me enough that I put

it back in the lathe and did more shaping until I was satisfied. This is not the only one that got

reworked. The cherry and maple one

started out with a raised top and the more I looked at it the uglier it

got. After expressing my concern and

sharing photos, the client agreed whereupon it got a haircut. Here are before and after photos of those

two.

The refrigerator magnets get sprayed with three coats of

satin lacquer and are left to cure for a few days to let the finish harden

before installing the magnets and their cups.

Those with sharp eyes may notice that the walnut and turquoise one is

missing. That’s because it had a small

blemish in the lacquer that needed to be fixed.

The parts used to install the magnet are its mounting

screw, cup and the magnet all shown at the top. The cup goes in first and is

screwed in place followed by snapping the magnet in place. Once the magnets are in, they are in to stay

as it’s nearly impossible to get them out of the cup.

I had a little trouble getting the first magnet cup to

fully seat in its hole so used a clamp and a small socket to press the cup in

until its firmly seated.

Because the box lid has a gloss finish the box will get

sprayed with the gloss lacquer I used when building my Les Paul SG electric

guitar back in 2012. Here is a photo of

it showing the finish. Side note – I

have built two guitars; an acoustic and this Les Paul electric. One lesson learned is I should stick to

building and not trying to play them.

It has been a long time since I used gloss guitar lacquer

and while it sprayed just fine it didn’t build quite as fast as the satin

lacquer that I now use. In order to get

the box finish to match the lid finish it took about six coats. When fitting the slot to the fit the lid I

worked to make it not so tight the lid would bind or not so loose that it falls

out. In order to keep the slot’s same

width after every other coat the slot required a little sanding to remove the

lacquer buildup. That’s done using a 6”

steel rule along with some 320-grit sandpaper.

At this point the outside of the box is completed but the

inside has one more step. To create a

nice luxurious interior all the inside surfaces get a black velvety

coating. Application is a multi-step

process starting by masking off the adjacent surfaces to keep the adhesive off

of them shown in the top photo. The second

step is applying a color matching adhesive to the areas. That’s not shown because once the coating is

in place the fibers need to be applied right away. Applying the fibers is done using an air pump

sprayer filled with the fibers that applies them evenly into the coating.

When done the box and lid finishes match plus the lids

slides just right. Here are a couple

photos of the completed box.

With all the various finishes applied everything is set

aside to allow them to gas-off, cure and harden before shipping. I am happy with the way all the different

pieces turned out. Even though I have

made a lot of the refrigerator magnets additional ones always give me a chance

to explore different options. Same with the Christmas ornaments so who knows I might try some more variations on them in the future.